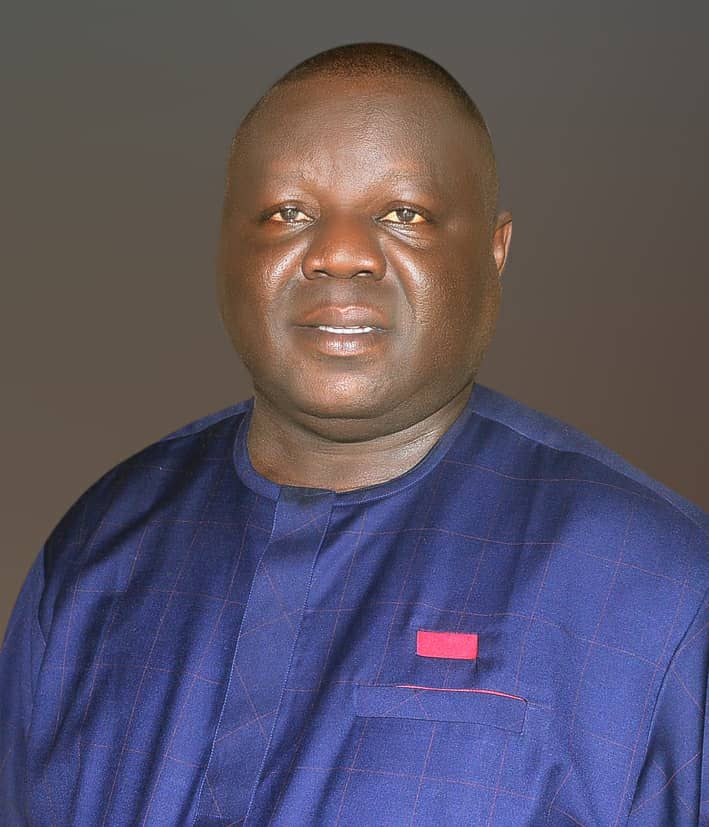

In this chat, Oyewunmi, the founder of Characom Leadership Consulting speaks on why leadership development is critical for Nigeria at this point in its history

Tell us a bit about your professional background.

I’m a leadership development consultant with a PhD in Industrial Relations and Human Resource Management. My academic journey has been shaped by a deep interest in leadership, organisational psychology, and human behaviour in the workplace. Over the past decade, I’ve built a global research network spanning Africa, Europe, and the Americas, with a focus on understanding and improving how people function within organisations. My work bridges theory and practice, offering both scholarly insights and actionable strategies. I’ve published peer-reviewed articles, which have been cited more than 700 times, and I serve as Associate Editor for two ABS-listed management journals, as well as on the editorial board of a leading social psychology journal. Teaching is another passion of mine. I embrace a ‘students as creators’ philosophy, encouraging learners to move beyond passive learning and become active contributors to knowledge and innovation. I currently lecture at the Teesside University International Business School. I’m also an author and editor. My edited book, The Dark Side of Leadership: A Cross-Cultural Compendium, is published by Routledge, and I’m currently working on another title. Beyond academia, I’ve consulted on leadership development for public and private organisations in Nigeria and the UK. I’m proud to be an Academic Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), and I continue to explore new frontiers in research, including a current project on whistleblowing behaviour in Africa with colleagues in the United States.

What inspires your work in leadership and organisational development, and how do you hope it impacts the next generation?

My inspiration comes from a deep belief that leadership is not just about occupying a position—it’s about influence, responsibility, and legacy. I’ve seen firsthand how poor leadership can derail potential, and how transformative leadership can uplift entire communities and institutions. This fuels my commitment to research, teaching, and consulting in this space. Through my work, I aim to challenge prevailing narratives and encourage a shift to transformational leadership, especially in contexts where the stakes are high. I want the next generation to see leadership as a service, not a status symbol —to be equipped with the tools, values, and global perspective needed to lead ethically and effectively. Ultimately, I hope my work contributes to building a culture where leadership is intentional, inclusive, and impactful—where young people are not just prepared to lead but inspired to lead well.

What are the major leadership problems in Nigeria?

The problems are multi-faceted. Nigeria faces several complex leadership challenges that are deeply rooted in historical, socio-political, and institutional factors. One of the most pressing issues is a lack of accountability and transparency in both the public and private sectors. This often leads to mismanagement of resources and erodes public trust in leadership. Another major concern is the dominance of transactional leadership, where loyalty is often valued over competence. This creates an environment where mediocrity thrives. It brings to mind Coleridge’s famous line: “Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink.” We have leaders in abundance, yet often without the depth or impact needed to drive meaningful change. This is why I’m so passionate about leadership development—because presence alone is not enough; substance matters. Ethno-religious divisions also play a role, as leadership appointments and decisions are sometimes influenced more by identity politics than by strategic national interest. This can lead to exclusion and a lack of a cohesive national vision. There’s also short-termism in policy implementation, where leaders focus on immediate gains rather than long-term development, which hampers sustainable progress. This is often compounded by fragile institutions that struggle to enforce checks and balances. There is a leadership development gap. While Nigeria has a vibrant and youthful population, there are limited structured pathways for grooming future leaders with the right values, skills, and global outlook. Addressing these challenges requires more than critique—it demands a commitment to cultivating ethical, visionary, and inclusive leadership at every level.

Why is leadership development critical for Nigeria at this point in its history?

Nigeria is at a defining moment. With a population exceeding 220 million, most of whom are under 30, we are rich in human potential. However, potential alone is not enough. We need leaders who can translate vision into action, who understand governance, and who are committed to inclusive development. Leadership development is the engine that can drive this transformation, ensuring that our future leaders are equipped with the skills, values, and mindset to lead ethically and effectively in a rapidly changing world.

Your recent work is ‘The Dark Side of Leadership: A Cross-Cultural Compendium’. How does this apply to Nigeria?

Yes, I am the lead editor of the book. It is a transdisciplinary venture that draws on the experience and scholarly apparatus of practitioners and researchers whose backgrounds cut across Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. The book is available on Amazon and at major bookstores worldwide. It sheds light on how leadership, when unchecked, can become toxic. In Nigeria, we’ve seen how power can be misused—whether through corruption, tribalism, or authoritarian tendencies. These are not just personal flaws; they are systemic issues that thrive in environments lacking transparency and accountability. The “dark side” is not always obvious—it can be masked by charisma or populism. I like to say that Charisma is not Character. That’s why leadership development must include ethical training and psychological insight, so leaders can recognise and resist these destructive patterns.

What are some warning signs of “dark side” leadership in Nigerian institutions?

There are several indicators. When leaders discourage dissent, centralise decision-making, or surround themselves with sycophants, it’s a sign of trouble. The book discusses how traits like narcissism and Machiavellianism can erode institutional integrity. In Nigeria, we often see this in the form of patronage networks, lack of meritocracy, and a culture of silence. These behaviours not only stifle innovation but also breed cynicism among citizens and employees.

How can leadership development programs address these dark tendencies?

By going beyond technical skills and focusing on character development. Programs must include modules on emotional intelligence, ethical dilemmas, and cultural competence. The book emphasises the importance of feedback loops and reflective practice—tools that help leaders stay grounded. In Nigeria, we must also contextualise training to address our unique socio-political realities, such as ethnic diversity, historical grievances, and institutional fragility.

Is leadership development only for those in politics or public office?

Absolutely not. Leadership is needed in every sphere—whether you’re a teacher, entrepreneur, community organiser, or civil servant. In fact, some of the most impactful leaders in Nigeria operate outside formal political structures. Leadership development should be seen as a lifelong journey that empowers individuals to influence positive change wherever they are.

What role should educational institutions play in cultivating leadership?

Educational institutions are the breeding ground for future leaders. They must go beyond rote learning and foster critical thinking, collaboration, and civic responsibility. Leadership clubs, student government, and service-learning projects are powerful tools. Moreover, educators themselves must model ethical leadership. If we want to raise a generation of responsible leaders, we must start by transforming our classrooms into spaces of empowerment and accountability.

How does culture influence leadership behaviour, especially in Nigeria?

Culture shapes our expectations of authority, communication, and conflict resolution. In Nigeria, respect for elders and hierarchical structures can sometimes discourage open dialogue or innovation. The book draws on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions to show how these dynamics play out globally. For Nigerian leaders, cultural intelligence is essential. They must learn to balance tradition with modern leadership practices, ensuring inclusivity while respecting local values.

What are some successful leadership development models in Nigeria?

There are several promising models. LEAP Africa, for instance, focuses on youth leadership and social innovation. The African Leadership Academy (ALA) nurtures pan-African leaders with a global outlook. The Not Too Young To Run movement has empowered young Nigerians to enter politics and challenge the status quo. These initiatives combine mentorship, experiential learning, and civic engagement—key ingredients for sustainable leadership development. However, these models must stay true to their vision and core values.

How can the private sector contribute to leadership development?

The private sector has a crucial role to play. Companies can invest in leadership pipelines, sponsor fellowships, and support entrepreneurship hubs. They can also model ethical leadership by promoting transparency, diversity, and corporate governance. When businesses prioritise leadership development, they not only strengthen their own organisations but also contribute to national development by producing leaders who are innovative, accountable, and socially conscious.

What role does mentorship play in preventing dark leadership traits?

Mentorship is a powerful antidote to the isolation and ego that often accompany leadership. The book highlights how mentors can provide honest feedback, challenge blind spots, and model ethical behaviour. In Nigeria, where formal leadership training is often lacking, mentorship fills a critical gap. It humanises leadership and reminds emerging leaders that power must be exercised with humility and responsibility.

How can we measure the impact of leadership development programs?

Impact should be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively. Are participants demonstrating ethical behaviour? Are they solving real-world problems? Are they influencing their communities positively? Long-term metrics might include reduced corruption, improved institutional performance, and increased civic engagement. Evaluation should be continuous, adaptive, and rooted in local realities.

What advice would you give to young Nigerians aspiring to lead?

My advice is both a call to courage and a cautionary tale. First, understand that leadership is not about titles or applause—it’s about responsibility, service, and the willingness to be held accountable. In The Dark Side of Leadership: A Cross-Cultural Compendium, the editors emphasise that even well-intentioned leaders can fall prey to destructive behaviours when they lack self-awareness, cultural sensitivity, or ethical grounding. Young Nigerians must begin by leading themselves—cultivating emotional intelligence, humility, and a strong moral compass. The book warns us about the dangers of narcissism, authoritarianism, and the seductive nature of power. These traits often emerge subtly, especially in environments where leaders are not challenged or held accountable. So, surround yourself with people who will tell you the truth, not just what you want to hear. Also, be culturally intelligent. Nigeria is a mosaic of ethnicities, languages, and traditions. Effective leadership here requires the ability to navigate diversity with empathy and respect. The compendium shows how cultural blind spots can lead to exclusion, conflict, or even failed reforms. Finally, embrace continuous learning. Leadership is not a destination—it’s a journey of growth, reflection, and adaptation. Read widely, listen deeply, and never stop asking yourself: Am I leading for the people, or for myself? If you can answer that question honestly and act on it, you’re already on the right path.